Extracts from The Journals of Three Ladies from Billerica, Massachusetts, in the Time of Our Civil War, 1864

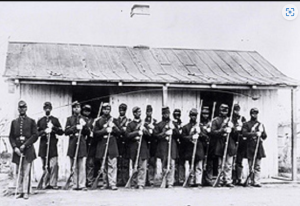

Three young ladies from Billerica, Massachusetts kept journals during the Civil War. These extracts from their journal entries record their experiences “while working as volunteers to work among the liberated slaves” at Camp Stanton, Benedict Maryland. This first-person account gives the reader a “bird’s eye view” in real time of what life was like for them and the African American soldier who volunteered to serve for the Union Army in exchange for their liberation. The journals start on January 13, 1864, and end on March 4, 1864, when the Union troops abandoned Camp Stanton. Camp Stanton was located in Charles County, Maryland on the western banks of the Patuxent River.

The following text is an extract from the Journals of Three Ladies

Permission to reprint from The Record. A Publication of the Historical Society of Charles County, October 2019 and May 2020 editions.

Extracts from the Journals of Three Ladies from Billerica, Massachusetts, In the Time of Our Civil War, 1864, Billerica, v.1-12, June 1912-May 1913. Billerica Printing Company, Billerica, MA

*************************************************************************************************

In the time of our civil war the ladies of Billerica held meetings, made garments for the soldiers, knit stockings, raised money, and did what the women all over the land did so nobly.

Miss Hannah Stevenson, of the Freedmen’s Bureau, called for volunteers to go South and work among the liberated slaves. Three Billerica ladies, Miss Eliza A. Rogers (ER), daughter of Calvin; Miss Ann R. Faulkner (ARF), daughter of James R., Miss Elizabeth Rogers (ER), daughter of Josiah, and two ladies from Concord, Mass., Miss Angelina Ball and Miss Jean Brigham, responded to the call.

They left Boston, Wednesday Jan. 13, 1864…A little after ten o’clock the next day they entered the mouth of the Patuxent River, and somewhat after midday on Wednesday, Jan. 20, 1864, they reached the wharf at Benedict, one week from the time they left Boston.

(A.R.F.) Well into the ambulance we gathered ourselves and through the deep mud over a corduroy road a black boy whipped tow lank horses for more than half a mile until on a high hill we were landed at the General’s headquarters and house combined. It commands a view of the camp and harbor and a fine view it is. The door through which we entered led into the keeping room. At the door stood Mrs. Birney with a very cordial welcome.

(E.R.) The house was formerly the residence of one of the wealthiest of the planters in this section, but such a house! There are two good-sized rooms on the lower floor. One of these is the General’s reception room and office; the other, the cooking room, dining-room and room general; from this an open staircase conducts to the two chambers above. One of these Mrs. Birney has generously given to the five ladies and taken all her family into the other, comprising the General, his wife and five children. What volumes this speaks for Mrs. Birney’s interest in the cause!

Imagine our room, twelve by fourteen, with a wall about seven feet on one side, sloping down to four on the other, with four French windows, a pane of glass out of one, and fine ventilation everywhere. As a compensating luxury we have an open fireplace with as much wood as we want. Mrs. Birney has given us dinner and tea, but tomorrow we must take care of ourselves. Few women could live as she does.

(A.R.F.) Jan. 21st. We have had an immense barn, formerly used as a tobacco press, fitted up for us today for a schoolroom in which it is intended to collect five hundred men at a time…

We have a little outhouse assigned us for cooking and eating. It has an immense fireplace but not even a window. That we are to have put in, but until our barrels arrive, our cooking, eating, sleeping and drinking are all done in one room. We form a rich scene for a painter.

(E.A.R.) The second day after our arrival we drew our rations: A whole leg and roasting piece of beef, a box of hardtack, enough for two mouths. D I should think; four candles, rice, good white sugar, tea and coffee. These are put in an outer room which is to be our kitchen. We have thus far lived in our room entirely, and it has been like camping out all the time, only more-so.

(E.R.) Jan. 22d. We started out directly after breakfast. The morning was lovely, very much like ours in April. The scene before us I could not describe. We stood beneath the Flag which has a significance here it never had before: below us lay the camp, the 7th, 9th and 19th Regiments, separated from each other by a little distance, and the blue smoke arising from each white tent, around which evergreens are tastefully planted, and on the broad plain beyond, between the camp and the wharf of Benedict proper, were squads of soldiers performing morning drill; their bayonets glistening in the sunlight, and still farther was the blue water of the Patuxent River. It was a lovely view…

Our school met from ten to twelve. Such eagerness to learn you can hardly understand, nor the surprising facility of some. They come in by companies, many of them fine-looking men, but it is so sad to think of their condition.

After school Anne Eliza and Miss Brigham went in an ambulance to the Southron [sic] plantation, where are the women and children whom General Birney is anxious to get clothed and sent to General Butler.

(E.A.R.) We found five men, twenty-one women, thirty-six children, besides six women, six small children and two men, who were friends and relatives of Colonel Southron’s slaves, and wished to go with them. It was our first view of slave life. Imagine a shed of one room with no window, but instead a square opening which could be closed by a sliding board, leaving the room dark. The chimney was outside at the end. We first encountered an old gray-headed negro, quite a shrewd, nice person. His was spinning rolls of her won carding, and several younger women were knitting socks and mittens which they said the soldiers would buy. Charles called all the women and children together who were in the quarters there. Then starting on his old white pony he rode to the lower farm, about two miles off, to call the people together there. The women were clean, though their clothes were very old and patched. The children were very destitute. We saw one baby, three days old, and I really should not have known it was not a white child. It was dressed in a dark calico dress with cheeked muslin sack, tire bound with buff and a white muslin cap. It looked quaint and cunning. The father, I was told, was a yellow man. They said they were all married by a minister there, and it was very seldom that one was sold off the plantation, yet they were all eager to go off and be free. Some of the girls about sixteen were regular wild Topsys

(E.R.) We had school from six to eight, then home to supper and all but myself to bed. It is past mid-night and I must close.

Jan. 23d. Went to school at eight o’clock. Should have enjoyed it very much if we could have had books. The poor fellows seemed so disappointed, and it is no easy task to teach a hundred men from two or three cards. The labor in itself is exhausting, and the consciousness that one just leaves so much undone is still more so…

(A.R.F.) Jan. 23d. The village of Benedict before the war had regular steamboat communication with various ports. It was an oyster place and a port for the export of tobacco. The three principal buildings of the village are used for the three regiments for hospitals.

Eliza, Lizzie and I visited the hospitals. I wrote a letter for one man. The men are very eager to hear reading. I asked whether they liked me best to read a story, a hymn, or the Bible. They all gave preference to the latter. I read in three different rooms. They prefer the Old Testament…One of the surgeons remarked that he would rather be among the black than the white sick men, for he heard not a word of vulgarity or profanity from them and they were very patient.

(E.R.) Jan. 24th, Sunday. About one o’clock Anne, Eliza and I started for the hospitals at Benedict, a mile distant. As I was leaving the house my attention was attracted to an old negro who was seated on a log surveying the troops who were out for weekly inspection. I asked him if he enjoyed it. Oh, he said I likes to look at Uncle Sam’s men.

Jan. 29th. The weather is charming, not a cloud have we seen since we came. We have three sessions of school now and the warm weather is rather enervating…We have witnessed battalion drill, which on such a lovely day as this could not look otherwise than finely.

Sunday, Jan. 31st. Another damp, foggy day. I have very unwillingly stayed in the house most of the day. I wanted very much to go to the hospital this morning and to hear the colored preachers this afternoon but must wait till another Sunday. Lieutenant Cheeney returned last night. He safely delivered the Southrons [slaves] to General Butler and saw them assigned, all tighter, to one of the best plantations, and left them as happy a company as possible. They are safely anchored at last on a farm where they will receive their first wages.

(A.R.F.) Sunday, Jan. 31st. I went to the convalescent ward of the 9th Regiment and talked or read with all the men there. Miss Ball came while I was there and joined in interesting the men. I am surprised at the ignorance of these men, even where they affect some little religious experience…I read to one set of men the ‘Commandments,’ the ‘Lord’s Prayer,’ and told them the origin and celebration of the ‘Passover.’ There is no mistaking their interest when telling them of such things…At two o’clock Miss Brigham and I started for the school room to attend ‘the colored meeting.’ The people began with singing, then prayer, quite low-voiced, and in no way attracting attention…’Set your house in order, for you shall died and not live.’ It was a respectable discourse in which the preacher stuck to his text with nothing about it striking or peculiar.

Feb. 2d. Inspection this a.m. caused school to be postponed, so we three cousins went to the hospitals at Benedict.

(E.R.) Tuesday, Feb. 2d. On account of a general inspection this morning we had no school. After breakfast Eliza and I started for the hospitals, where we passed the forenoon. In going there we cross a march on which planks have been laid for pedestrians, but when the tide is high it is hardly passable. As we reached the place we found a negro who had put down his basket and bundle and waited until we came up that he might help us across, which he did in such a respectful, gentle way, saying, ‘My Misses always taught me to be tender of the ladies.” IN the 9th hospital I found four men had died since my last visit.

Feb. 3d. We heard last night that the camp was to be broken up here in about two weeks and the troops to be3 sent into the field. It is difficult to know anything certainly here, and we probably shall not know about our leaving until it is time to pack knapsacks…

(E.A.R.) We went to every negro hut we could. First we found a family of free blacks. The father got his living by oystering. They said they were comfortable save that their house was very cold. It was full of cracks where you could look out of doors. Not a glazed window did we find in any habitation, and we went to six different ones. The doors stood open or else they were in darkness except where there was an opening which could be closed by a wooden shutter. The free blacks paid $15 yearly rent, generally in labor.

In the second family we found a woman and four children. Her husband, a slave, died last autumn. She said she had got along comfortably so far with what money he left her and what washing she could get to do. When he was living he worked for his master all the time, except a short time at noon, at breakfast, and in the evening. He was furnished with clothes, a half-bushel of meal, and three pounds of meat once a fortnight.

(E.R.) In one cabin we found a group of four little black children sitting on the hearth with their little black toes drawn up to the warm ashes. The oldest might have been eight years, and in her arms was a babe of a few months, and in a box in the chimney corner, covered with a mess of rags, was a tiny baby of a month or two, asleep. Here were six little ones and quite a picture they made.

They said their mother’s name was Julya. We commended the motherly little girl for taking care of so many, two of them her cousins, and wont on.

We went around among the Moulton slaves and the contrabands. We found one poor woman who had come from over the country, whose life had been a hard one. All her children had been sold from her when young—with one exception. She is now alone and doing very well in taking washing from the soldier. All the water has to be ‘toted’ on their heads or in buckets from the ravines up the steep hills. The houses have no windows and we asked if they could keep warm. They said, ‘Oh no, not in cold weather.’ We should think animals would suffer with so little protection…Tomorrow we shall try to distribute clothing among these poor people. The contrabands must all be hurried away from here, for after the troops leave they will suffer from the rebels.

(A.R.F.) Feb. 4th. When talking with the young men at dinner about the experiences of the morning they said we could see nothing of the effects of slavery here, it had existed in a mild form, but go to Georgia if we wanted to see what it was…

Talk about discomfort for us, why, we have not known anything but luxury. We have not tried anything yet that has not provoked mirth rather than a groan. We ‘give up’ and ‘come down’ daily in our fancies and notions, yet we could part with a great deal that we have now and yet not suffer in the least…

(E.R.) Camp Stanton, Feb. 5, 1864. Anne and I called on Mrs. Thomas and then with a bag of clothing we started for Julia’s house were we saw the six little black children. We made the mother’s heart glad by giving to each child something, and to the oldest we gave the little doll that Belle Talbot sent to ‘some little black girl.’

Saturday, Feb. 6th. After breakfast we went to witness dress parade, which was finely done. On the field we were introduced to Captain Granville who said he had been to Billerica. From school, Eliza Anne and I went to visit the neighboring plantation of Mr. Sly. The Sly mansion has rather more of the Southern elegance than any we have seen…Everything about had, what Yankees would call, a shiftless appearance.

(E.A.R.) I came home and had just time to distribute some clothing to the women from the 9th hospital, and then to dinner on soup, coddled beef, bread and butter.

(E.R.) Sunday, Feb. 7th. At nine o’clock Miss Ball and I started for the hospital, where we stayed till after twelve. As usual, I enjoyed the time spent there very much. The men seemed delighted and to me it is better than any sermon I ever heard.

After dinner we went to the barn anticipating much novel pleasure in hearing the colored preachers. Instead we had regular services, a sermon from Mr. Higginson and music by the band…

At supper we sat a long time at table hearing scraps of experiences from Yorktown, Gettysburg and the Peninsular campaign…

This has been our third Sunday in Camp Stanton. We are gaining an experience here that money would not buy, and we really have been deprived of nothing absolutely necessary to us.

(E.A.R.) After repeated experiments we have come to the conclusion that the only way to teach these men (the time was short) is to give them a primer, help them to pick up their letters as best they can, and then set them to spelling out easy words. Many of them will never learn to read, but they pore over their books so earnestly it makes it all the more pitiful. More than half will preserve and learn to read a little if they have anything of a fair chance.

(A.R.F.) Feb. 9th and 10th. Went from a.m. school direct to Benedict hospital. In one room where I spent more than an hour reading, writing, and showing men how to read, write, and spell names, was a very sick man. I thought he must be disturbed by reading…After reading a few minutes I went to him and asked him if reading disturbed him. ‘I loves it,’ he half whispered…

(E.R.) Thursday, Feb. 11th. The condition of the fugitives as they come in here for protection is very sad. One poor woman came in last night with two children, one of them a boy of ten years from whom she had been separated most of the time for four years. This morning another little baby was added to her cares.

Mrs. Birney has named it Stanton Freeman. We take quite an interest in it. How rich is our experience here! The information we gain here could not have been acquired in any other way…I shall always look back upon it with satisfaction.

Camp Stanton, Feb. 12th, Friday. Last night we received intelligence from the General that he brought orders from Washington for the 7th and 9th to march on Monday. We feel badly enough…

Only the 19th will be left…But the movements of the regiment are uncertain and we may leave any time. All will now be hurry and bustle for three days. They go from here to fortress Monroe; beyond that their destination is not known. Many of the men must fall, for they are without doubt to go immediately into active service, and in all probability many of the officers will not return. They feel this and calmly talked of it this morning at table. They are all veterans and with the experience of Harpers Ferry, Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, and many other perilous events they know what is before them. They say they will never be taken prisoners, but will conquer or die…

Saturday, Feb. 13th. We had no opportunity to teach until tonight for want of pupils. This being the general washing day, added to the preparations for moving, quite broke up our school.

At school tonight one of my men, who has been zealously trying to learn to write, seemed to feel quite badly that he should not come again and expressed much gratitude at the opportunity that had been given him. He was quite delighted when I told him that as soon as he had learned to write he must send me a letter away up to the North.

(E.R.) Sunday, Feb. 14th. I went to the hospitals in Benedict. I was afterwards joined there by Eliza, who had been to witness the presentation of a flag to the 7th by the colored ladies of Baltimore. Only the sickest of the men are left in the hospitals, the rest are returned to camp…

Monday, Feb. 15th. When we woke this morning ink and water were frozen, medicine bottles burst, and the air was whizzing about our ears with cutting severity. It was too cold at the barn for any more than could gather about the two fires. Finding my services would not be available there, I wrapped myself in as much clothing as I could carry and started for Benedict. I had the wind in my back, and got there very nicely. I went through every room of the 19th and 9th, and about two o’clock, as I was in an upper back room, who should come in but Captain Post and his splendid dog, Charley. He said he feared I should perish on the plain, and he came for me with a thick shawl. The cold has increased so much that even with his help I thought I should freeze my hands and face.

(A.R.F.) Feb. 17th. Last night I had a new pupil, a great stalwart man. He had been ‘detailed’ for the bakery at Benedict and had seen e there. He had come back to camp to move with his regiment. He asked where they were going; then he says, ‘But what shall we do about our wives?’ I asked if he would like to have me write to his wife. I wrote by his dictation a touching letter. Among other things he says, ‘Pray for me and believe that God will do all right. If I should not see you in this world, I trust to meet you in heaven. I have thought much of delivering you from the house of bondage. The colored people have a great privilege here in having teachers, and they are white ones too.’ After concluding messages he says, ‘Miss, make it as long as you please and as much like heaven, as I know you will know how.’ …A man named Azariah says to Eliza, ‘If I had ten dollars all in gold I would give it to have the school remain.’ He believes the Lord has led every step of his life. His trusting faith manifests itself in all his manner.

(E.R.) Feb. 18th. Today is equally cold and as wood is getting scarce we had but one fire at the barn and that only for a little while…I wrote two soldiers letters and taught whoever came…It is too cold to do anything. We have been pasting newspapers over the cracks and hope this evening to be a little more comfortable…We have no definite news tonight as to the arrival of the transports.

Camp Stanton, Feb. 19th. The weather is intensely cold and we have had no school. Eliza, Anne, and went to Benedict. We went to see Harriet Dorsey, a colored woman whose history has interested us greatly, and from there to the 9th hospital…Now that the troops are a bout to leave, great numbers of fugitives, women and children, come in and try to get a pass to Washington. This the General has no power to do officially, and it is very hard to tell them their only hope is to get to Washington as best they can by night. I am convinced that no stories that have ever been told of the sufferings of this people are half equal to the truth.

Monday, Feb. 22d. We resolved to have school if possible, today, but found there was no hope of that. I spent two hours at the hospital, as it is now confidently asserted that we shall depart on Wednesday. We shall try once more having a reception for our kind friends. They say we know very little of the pleasure it gives them to have a taste of civilized life once in a while.

(A.R.F.) Feb. 25th. This a.m. we received a most complimentary present from a man at the hospital. A rap at the door, which Cousin Eliza answered, and there stood a colored man with a waiter in his hand, on which was a plate of cake and a knife beside it, all neatly covered over with a new huck-a-buck towel. He said he had taken the liberty to bring the ladies a present all on his responsibility; they had been so kind in visiting the hospital so much he wished to show his regard for them. It was one of many touching appreciations of our slight efforts for a truly grateful people.

(E.A.R.) Sunday evening, Feb. 28th. I have been down to the hospital this afternoon. One of the nurses, Stephen Bailey, whom I am teaching to write, gave me something of his history. He is forty-six years old has left a wife and many children. He says he has had eleven ‘head’ of children, two are dead, nine are still living. He always fared will in his master’s house, lived in the kitchen and had a plenty of food from his master’s tables. His wife was hired out as cook on a neighboring plantation and used to keep two of the youngest children with her. The others as soon as they were old enough were hired out. His wife was clothed, also the two children about ten or twelve dollars per year were paid for her services. The last year she had three children with her, so no money was given her. He said, though she was the mother of eleven ‘head’ of living children, her master never so much as gave a blanket or a Sunday dress, or even her head handkerchief to her. But he had always been able by working nights and holiday to keep them in Sunday clothes and have a little money in his pocket.

March 2d. After dinner I went to Benedict—found such a welcome there that I came home happy…As I reached the hospital, I saw for the first time a burial procession. Four soldiers walked with guns reversed preceding the coffin borne on the shoulders of four men… I turned to enter the 19th hospital. On the front piazza were four dead men wrapped in their blankets…I found only one room of sick men and some of these so sick that I would not stop in the room…I went into the 9th. In the first room I taught a group of men to play a game of picture cards. It was Eliza’s suggestion that I take them, and a happy hit it proved.

Entering another room, one man was reading aloud from a Methodist Hymn Book. He stopped, but I asked him to proceed; after he had read, I read several hymns. He brought me his slate to write his named ‘Levin Morris.’ Then I recognized the man whose queerly compounded prayer had so interested me at meeting.

(A.R.F.) March 3d. We passed through the hospitals to see the half-sick men waiting beside the fire, knapsacks on the floor, all ready to be put on board the boat. I presume a score or more of them will find a quiet rest for their weary bones before the transport reaches Hilton Head.

Then we found a man, named Vernal Hawkins, in whose welfare we are much interested. He told us that his wife and five children had escaped from slavery two days before and he must go, doing nothing for them. He had given his wife all the money he had, and if we could do anything for them, he should be so grateful. We went to see her and told her to come to headquarters to see us. She came with three other women and we gave her what we had to spare and told her to pack her bundle and be in readiness tomorrow a.m. and if we could get her on board we would do so. At noon the General said there should be a boat tomorrow for Fortress Monroe and all the women and children we could get on board should go. So after dinner Eliza started for Benedict to spread the good tidings.

(E.R.) March 4th, Friday. Yesterday morning there were in the camp and connected with it at Benedict about three thousand persons; now there is not a person left in the campground.

The Kingston mansion, where we had lived, is vacant, ready for its rebel owner, who will doubtless take possession as soon as the General is fairly out of sight. There are to be left at Benedict fifteen persons, too sick to be moved, in the care of one surgeon, and one company from the 19th is left to guard them.

The news spread like fire and all who wanted to go off came flocking in and were taken on board the Cecil. About twelve o’clock we moved away from Benedict and had our last look of the deserted place…Before starting we went on board to see how the men were stowed away. It was very pleasant to see the leased look of those who had been our pupils; they seemed so glad to see us once more. Colonel Shaw parted with his wife there, but the General and Lieutenant Purington went on with us to the mouth of the river, which we reached at five o’clock. There the two boats came alongside, the last good-byes were said, and the General was off. The transport went down the bay bearing her freight of a thousand souls, and we came north. Handkerchiefs were waved until they were out of sight. It was a hard time for Mrs. Birney, but she bore it bravely. She is a wonderful woman.

I am very thankful for all we have seen and learned, and though our labors were cut short just as we were fairly established, yet everyone bears testimony that our coming has not been in vain. I cannot but feel that we have given these men a stimulus to future effort, and they have been so grateful for the interest taken in them. It is our plan now to be in Washington tomorrow night, remain there till Tuesday, and be at home sometime before Saturday.

*********************************************************************************************

Did You Know:

John F. Butler from St. Mary’s County Greenwell Plantation was among the “Colored Troops” stationed at Camp Stanton during the winter of 1864. His story is included on this website.

William H Coates 18 and William B. Jones 19 from the farm of George Peterson

Additional Resources

“Training For Equality: The Story of Camp Stanton,” the latest installment of the award-winning documentary series “Deep Roots & Many Branches: The African American Experience in Charles County.” “Training For Equality” recounts the story of Camp Stanton, a training base for black Union soldiers in Benedict that began operations in October 1863.

Camp Stanton Documentary Honors Black Civil War Soldiers by Charles County Government, Baynet, August 3, 2024.

Camp Stanton and the U.S. Colored Troops, by Patricia Samford, History by the Objects, Jefferson Patterson Park, February 11, 2021.